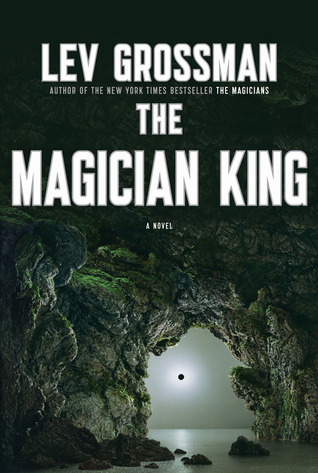

Please enjoy this excerpt from Lev Grossman’s The Magician King, out today from Viking. This novel is a sequel to The Magicians, a story set in a world full of magic that contains many allusions to other books full of magic. Lev Grossman wrote up a complete guide to all of these sneaky allusions here.

***

CHAPTER 4

You have to go back to the beginning, to that freezing miserable afternoon in Brooklyn when Quentin took the Brakebills exam, to understand what happened to Julia. Because Julia took the Brakebills exam that day too. And after she took it, she lost three years of her life.

Her story started the same day Quentin’s did, but it was a very different kind of story. On that day, the day he and James and Julia walked along Fifth Avenue together on the way to the boys’ Princeton interviews, Quentin’s life had split wide open. Julia’s life hadn’t. But it did develop a crack.

It was a hairline crack at first. Nothing much to look at it. It was cracked, but you could still use it. It was still good. No point in throwing her life away. It was a perfectly fine life.

Or no, it wasn’t fine, but it worked for a while. She’d said good-bye to James and Quentin in front of the brick house. They’d gone in. She’d walked away. It had started to rain. She’d gone to the library. This much she was pretty sure was true. This much had probably actually happened.

Then something happened that didn’t happen: she’d sat in the library with her laptop and a stack of books and written her paper for Mr. Karras. It was a damn good paper. It was about an experimental utopian socialist community in New York State in the nineteenth century. The community had some praiseworthy ideals but also some creepy sexual practices, and eventually it lost its mojo and morphed into a successful silverware company instead. She had some ideas about why the whole arrangement worked better as a silverware company than it had as an attempt to realize Christ’s kingdom on Earth. She was pretty sure she was right. She’d gone into the numbers, and in her experience when you went into the numbers you usually came out with pretty good answers.

James met her at the library. He told her what had happened with the interview, which was weird enough as it was, what with the interviewer turning up dead and all. Then she’d gone home, had dinner, gone up to her room, written the rest of the paper, which took until four in the morning, grabbed three hours of sleep, got up, blew off the first two classes while she fixed her endnotes, and went to school in time for social studies. Mischief managed.

When she looked back the whole thing had a queer, unreal feeling to it, but then again you often get a queer, unreal feeling when you stay up till four and get up at seven. Things didn’t start to fall apart till a week later, when she got her paper back.

The problem wasn’t the grade. It was a good grade. It was an A minus, and Mr. K didn’t give out a lot of those. The problem was—what was the problem? She read the paper again, and though it read all right, she didn’t recognize everything in it. But she’d been writing fast. The thing she snagged on was the same thing Mr. K snagged on: she’d gotten a date wrong.

See, the utopian community she was writing about had run afoul of a change in federal statutory rape laws—creepy, creepy—that took place in. She knew that. Whereas the paper said, which Mr. K would never have caught—though come to think of it he was a pretty creepy character himself, and she wouldn’t be surprised if he knew his way around a statutory rape law or two—except Wikipedia made the same mistake, and Mr. K loved to do spot-checking to catch people relying on Wikipedia. He’d checked the date, and checked Wikipedia, and put a big red X in the margin of Julia’s paper. And a minus after her A. He was surprised at her. He really was.

Julia was surprised too. She never used Wikipedia, partly because she knew Mr. K checked, but mostly because unlike a lot of her fellow students she cared about getting her facts right. She went back through the paper and checked it thoroughly. She found a second mistake, and a third. No more, but that was enough. She started checking versions of the paper, because she always saved and backed up separate drafts as she went, because Track Changes in Word was bullshit, and she wanted to know at what point exactly the errors got in. But the really weird thing was there that were no other versions. There was only the final draft.

This fact, although it was a minor fact, with multiple plausible explanations, proved to be the big red button that activated the ejector seat that blew Julia out of the cozy cockpit of her life.

She sat on her bed and stared at the file, which showed a time of creation that she remembered as having been during dinner, and she felt fear. Because the more she thought about it the more it seemed like she had two sets of memories for that afternoon, not just one. One of them was almost too plausible. It had the feel of a scene from a novel written by an earnest realist who was more concerned with presenting an amalgamation of naturalistic details that fit together plausibly than with telling a story that wouldn’t bore the fuck out of the reader. It felt like a cover story. That was the one where she went to the library and met James and had dinner and wrote the paper.

But the other one was batshit insane. In the other one she’d gone to the library and done a simple search on one of the cheapo library workstations on the blond-wood tables by the circulation desk. The search had yielded a call number. The call number was odd—it put the book in the subbasement stacks. Julia was pretty sure the library didn’t have any subbasement stacks, because it didn’t have a subbasement.

As if in a dream she walked to the brushed-steel elevator. Sure enough, beneath the round white plastic button marked B, there was now also a round plastic button marked SB. She pressed it. It glowed. The dropping sensation in her stomach was just an ordinary dropping sensation, the kind you get when you’re descending rapidly toward a subbasement full of cheap metal shelving and the buzz of fluorescent lights and exposed pipes with red-painted daisy-wheel valve handles poking out of them at odd angles.

But that’s not what she saw when the elevator doors opened. Instead she saw a sun-soaked stone terrace in back of a country house, with green gardens all around it. It wasn’t actually a house, the people there explained, it was a school. It was called Brakebills, and the people who lived there were magicians. They thought she might like to be one too. All she would have to do is pass one simple test.

The Magician King © 2011 Lev Grossman